It’s August 2021 when Matteo Della Bordella, Silvan Schüpbach, and Symon Welfringer reach the east coast of Greenland. The three are among the most skilled alpinists on the international scene. Matteo is a visionary seeker of lines whose experience includes expeditions and extreme climbs all over the world; Silvan knows the hardest walls in Switzerland and the Alps like the back of his hand; and Symon’s résumé boasts a Piolet d’Or, the highest honor in the mountaineering world. All three share a passion for adventure and the desire to climb “by fair means,” tackling high-level difficulties with a clean style that attempts to leave as few traces as possible on the mountain.

In Greenland they choose an immersive experience, tackling a long crossing by kayak in the Arctic Ocean to reach a high and difficult wall in a remote environment where they can seek to reach their full potential, far from human constraints, rediscovering an authentic connection with the wilderness.

GREENLAND PART 1 – WHERE THE SUN DOESN’T SET

As in a mosaic of bright hues, the houses of the village of Tasiilaq begin to appear one after the other behind the hill. They form a vibrant picture of small colored boxes. “Here we’re in their home,” a sign on the door of the Red House reminds us. Robert Peroni welcomes us with a smile full of enthusiasm. His face is marked by wrinkles rich in experience. On paper 40 years separate us, but our ideas and ambitions are the same. Born in South Tyrol, Robert, after 20 years of exploration and extreme climbing, has chosen to make this small town on the east coast of Greenland his retreat. A harsh and wild land inhabited by the Inuit, a people whose culture has long been threatened by the arrival of modernity. When Robert reaches this land, he finds individuals who need support, both material and psychological. He welcomes them in an old house, which year after year is transformed into a small hotel for tourists on northern expeditions. The famous and welcoming Red House.

“The last few years haven’t been easy at all,” he says as the heat inside begins to warm our bones. “The pandemic stopped everything.” The virus did not come here, bringing the deaths that we all still remember clearly, but it did dry up the economy.The east coast of Greenland was isolated for a whole year, he tells us. Without supplies, food began to run low, while even today the absence of tourism continues to damage the entire local community. But Robert is not the type to give up at the first sign of hardship. He likes a challenge; I can see it in his bright eyes.. “So, what do you have in mind?” he asks us. The table fills up with maps. Notebooks are covered with sketches. Robert is a torrent unleashed. Outside the window, the elements rage. A primordial force is revealed before our eyes. At the same time, I feel a shiver on my back and a lump in my throat imagining ourselves out there. Me, Silvan Schüpbach, Symon Welfringer, and nature at its most extreme.

Silvan is Swiss, and we’ve already shared immersive experiences like this together. In 2018, in Patagonia, when we managed the first ascent of a new route on Cerro Riso Patron Sud after having tackled a kayak crossing of about 100 kilometers and a long approach through remote territory. All, of course, fully self-supported. Symon is French, and this is the first time we’ve gone on an expedition together. His mountaineering résumé places him among the best climbers in the world, and he has a wry sense of humor. Always accompanied by his faithful Hawaiian shirts, he’s an extremely strong climbing partner. Robert’s eyes penetrate us as we recount our plans. For him, we have no secrets. Who knows what he’s thinking, with that silent but concentrated expression. More than 150 kilometers in a kayak, 70 kilos of supplies per person, an unclimbed wall. Pure adventure! Silvan, Symon, and I form a tight-knit trio, and even Robert has noticed it. We speak as one.

THE OCEAN BY KAYAK

At the port of Tasiilaq, we spend half a day just to prepare our kayaks.We must divide the loads well and ensure that each kayak is well balanced.. AWe have a total of 210 kilos of food, climbing and camping gear, clothing, and other equipment. We can’t leave anything to chance; once we leave, we’re on our own until we return.. If preparing the backpack before a climb is an art for every good mountaineer, the same holds for us in preparing our kayaks for 25 days of completely self-supported expedition. Each piece of our equipment has been chosen with the utmost care to limit weight and bulk. We have with us the bare minimum: two changes of clothes in which we place our complete trust. Pieces that are warm and breathable but at the same time highly compactible, like the K-Performance Fleece. It weighs only 350 grams and is a second layer that offers an outstanding balance between warmth and compactibility.

With the sun unable to set over the horizon, we let our kayaks slide slowly out of the harbor and start paddling on the ocean. I’m relaxed and happy. I feel free. I no longer depend on external forces or agents. Now I’m master of my destiny, and in front of me I have the infinite space of the Arctic Ocean.. We are on our way to the Mythics Cirque. The fortunate combination of good fitness, exceptional kayaks, and perfect sea conditions makes life relatively easy for us. Every day we paddle for about seven hours, managing to cover a distance of 40 kilometers. All these hours in the kayak are strenuous and require intense and prolonged effort. Dry suits protect us in the event of a fall into the freezing Arctic waters, but at the same time they make us sweat and dehydrate very quickly. To try to stay dry under the suits, we wear Croda Rossa jerseys, which thanks to their breathability keep us dry even after hours of exhausting paddling.

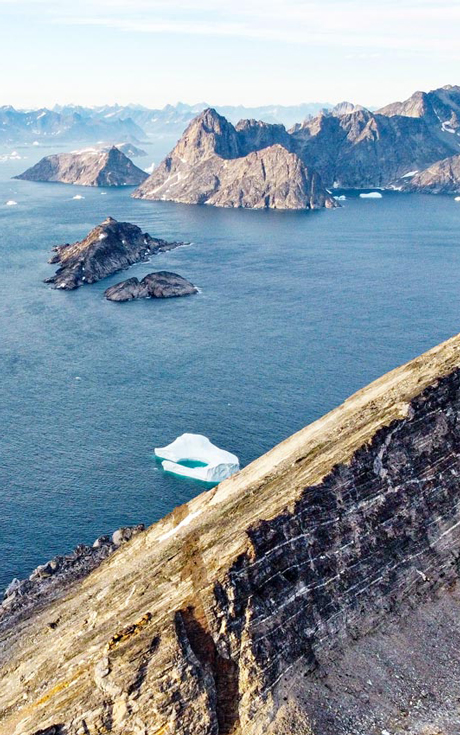

The days go by quickly, one after the other, paddling between giant icebergs under the watchful eyes of seals. They seem intrigued by our passage. Every evening we camp on the coast, often in idyllic places. True corners of paradise, with fresh water and an unparalleled view of the ocean, which we manage to find despite our improvised navigation. The vistas repay every effort, even when, after 100 kilometers, Silvan begins to suffer from an annoying arm pain. But now there’s no time to lose heart and, gritting our teeth, after four days, here we are finally facing the walls of the Mythics Cirque.. In front of us an amphitheater of vertical and overhanging rock opens up. In our minds, lines and tracks that ascend rapidly to the top are already taking shape. The first human footprints are hundreds of kilometers away.

But wait! Who are those four? On the coast, naked as the day they were born, Sean Villanueva, Nico Favresse, Jean Louis Wertz, and the Swedish climber Alexsej Jaruta welcome us with the sound of music. What are the chances of meeting a group of friends in one of the most remote and isolated places on the planet? They arrived four days before us, on a sailboat, also intending to explore the virgin rock of the Mythics Cirque. A real surprise, and a great pleasure, to meet friends. Very strong mountaineers who share our same style, but who above all experience the mountains in such an exuberant way even here, at the end of the world. A dinner and lots of laughs are enough to make us feel at home after long days in the kayak. Then we fall asleep watching the increasingly small silhouettes of our friends heading toward the great walls. Finally, the time has come also for us to put away our kayaks, paddles, and dry suits and look up.

GREENLAND PART 2 – THE CALL OF THE SIREN TOWER

Before setting out on this expedition, we analyzed the few photos that we’d managed to obtain of the Mythics Cirque, and the imposing vertical north face of the Siren Tower immediately captured our attention. It was definitely the most attractive, aesthetic, slender, and compact of the walls offered by this magnificent amphitheater in which we find ourselves. The spark is immediate, and the decisionmade. Let’s try to climb it!

After taking a few days to recover from the kayak trip, we take advantage of the stable weather to attack the wall. We bring food for six days, 40 liters of water, and three inflatable portaledges. The latter are useful for setting up a bivouac on the wall, allowing us to rest “in comfort. We want to enjoy this climb, without forcing the pace too much and without any rush to attain the result. We’re here to experience an adventure, to fully enjoy the environment and the climb. In the first two days, we climb the first 300 meters of the face. In a rhythmic way we climb and retrieve the heavy bags with the equipment, which remain hanging on the ropes while we climb so as not to weigh us down too much. We are confident that we’ll beable to do well, but we also know that the hardest part is still to come: in front of us looms the most vertical and steep section. One look upward is enough to feel awe atthat compact rock. We observe it for a long time, after having made ourselves comfortable for the night. The questions that crowd our thoughts are many and repetitive. Doubt begins to creep into us. Suddenly, nothing seems sure to go right anymore. In the meantime, the sky doesn’t seem to want to hand over our thoughts to darkness.

When we wake up, on the third day, Silvan complains of a severe pain in his arm. It’s the same issue again that he already experienced while kayaking. Until today he’s pushed ahead, trying to ignore the problem, but now he can’t manage it any longer. Symon, as always, looks at us with his calm smile. He’s motivated and confident. Without a second thought he sets off toward the top and, after several attempts, manages to climb a thin 10-meter long crack. A sequence that’s more than delicate, protected only by micro-nuts of dubious strength. There’s only one rule: don’t fall! Beyond the crack it widens and gives us false hope of easy climbing. I load all the material and try to continue.

The first moves come easily, then, centimeter by centimeter, I see the space to place protection constricting more and more. The crack becomes progressively narrower, until it ends after about 10 meters. I’m torn, but I have to continue with aid climbing, a slow and laborious style that’s vastly different from my approach to the vertical world.

Under certain conditions, you have to make a virtue of necessity and arm yourself with patience and steadfast nerves. It takes two and a half hours of attempts — characterized by exertion, scares, and meticulous vertical carpentry work — to reach a new crack where I can place two excellent friends that allow me to breathe, andfree the next 5 meters that lead to an evident dihedral.

Here’s where our day ends.We’re exhausted from climbing. It’s taken us four hours to climb 23 vertical meters. The road ahead is still long, and, looking up, we feel conflicting emotions, as we do every evening now. Maybe, we think, we should give up. But this is not the time to think about the future. We’re tired and need to rest, so we descend to the portaledge, where we find Silvan, with a steaming dinner, wrapped in his Artika jacket. Soon I too let myself go in the relaxing warmth of natural down. The heat enters my body and my muscles relax as the endorphins take effect. The Artika is an extremely comfortable and warm down jacket, which we’ve chosen to bring with us because its outer membrane is resistant to abrasions and rubbing against the rock — the terrain we’re in contact with practically 24 hours a day. Before going to bed we have to assemble the other two inflatable portaledges, large reinforced mats to hang on the wall. The night hours are basically the only time when we can relax, and to rest well it’s important to have a minimum amount of space that allows you to lie down and let your muscles release tension.When we try to inflate them, we immediately see that they aren’t holding air. They have holes! Our morale, already low, now plummets down the wall. We spend hours trying to find an unlikely solution to avoid an unbearable bivouac hanging from our harnesses, but nothing seems to work. There’s no way to inflate those two mats, and with each failure the frustration increases. Symon yells into space to release the tension, and the Belgians answer him from above. Our guardian angels! They’re descending after completing the first ascent of a route that runs parallel to ours on the right side of the north face of the Siren Tower. “Sean! Nico!” Our joyful screams bounce off the walls. “Matteo! Symon! Silvan!” They respond. We quickly manage to agree on the loan of a portaledge. They’ve completed their ascent and won’t need it anymore for a few days. We set it up in a matter of minutes, while we listen to their story. Then, finally comfortable on a horizontal plane, we watch them glide rapidly downward. They disappear into the void, and we’re able to smile again.

THE HARDEST DAYS

Fourth day on the wall. The environment is incredibly calm, and there’s not a breath of wind. The only sound is the rattling of our hardware hanging from our harnesss. It’s freezing, and I’m happy to be wearing the K-Performance Mountaineer pants. Since I first tried them, more than three years ago, I think I’ve taken them with me on every expedition. From Patagonia to Peru, from Greenland to the Himalayas. The hardest part of the climb opens up ahead, and there are only two of us. Silvan is recovering but is still unable to tackle difficult pitches. I take the initiative. I climb a first pitch that is not particularly difficult but tricky to protect. Reaching the rest point, I prepare to hand over the lead to Symon, but my French friend prefers to let me go first. Once again I look up into the unknown. The wall becomes overhanging, the cracks slightly flared, always discontinuous and increasingly distant from each other. I start without conviction and climb the first few meters with difficulty; then, in search of a foothold, I loosen a rock that falls on Symon’s leg, causing him scream in pain. Just a blow, nothing serious, but here the entire climb is at stake. For a moment I’m assailed by negative thoughts, which I manage to dismiss by looking at Symon’s confident smile. His ability to stay calm impresses me. I set my tiredness aside and turn off the negative thoughts that are haunting me, trying to focus solely on the climb and the square meter of granite in front of me. I manage to place some excellent protection, but after a short sequence of moves I already see them too far below me. I reach out to place an Alien in a flared hole … more for psychological help than anything else. I know it couldn’t hold a fall, but having it there allows me to relax my mind and muscles. I load a part of my weight on the protection and spend seemingly endless time shaking the fatigue our of my arms before starting again.

“If it doesn’t hold, we’re in trouble,” Symon comments as soon as I start, but by now it’s too late for me to be influenced. climb up a nice crack, where I finally manage to secure bombproof protection. I follow it faithfully upward, without the possibility of error.My muscles are strained to the maximum, my mind focused on every move. A very hard pitch. Reaching the end is a release. I’m drained of all energy, but looking up I can finally smile: the route to the top, although long, does not present any major obstacles. We hear Silvan’s voice from the portaledge; he’s delighted with our success, and when we reach him he welcomes us as if we were already at the top. His arm is better, and tomorrow he wants to get his hands on the rock to complete what we started together.

THE TOP!

The fifth day on the wall is the most strenuous so far. The long, hard hours of climbing the day before have left their mark, so I put myself in “energy saving” mode by simply following my companions to the top.

We climb back up all the fixed ropes, up to the point we reached yesterday, and then Symon attacks. He and Silvan alternate the lead until they cover the remaining 300 meters of wall to the summit. We reach it in the afternoon. When we’re all at the top we can finally look up at the horizon. An incredible panorama, a 360-degree view that repays us for everything that the climbing has demanded of us in the last few days. What amazes us are not the icebergs or the vastness of the ocean from which we arrived, but the privileged view of theimmense Greenland ice sheet that extends as far as the eye can see beyond a multitude of still unexplored peaks. I’m filled with a sense of peace and harmony that makes me feel strangely in tune with this land. For a moment, my restless and never-satiated soul finally finds satisfaction on top of an unknown mountain. For a moment, I live in the present.

GREENLAND PART 3 – DESCENT, EXPLORATION, AND RETURN

The night that doesn’t want to come and the endless panorama make us lose track of time. I don’t know how long we stay at the top of Siren Tower. We’re completely absorbed, and we almost have to force ourselves to prepare the rappels that will take us back to the bleak north face to return to the portaledges. When we reach them, we ask ourselves what we should do:descend and conclude our experience here, or continue climbing to free all the pitches we’ve aid climbed. In reality, there’s very little to discuss; the decision has already been made. So we go to sleep, ready for a new day of climbing. Being able to free climb the crux pitch of the route, after all the effort made to complete the first ascent, would be the icing on the cake of a great experience.

THIS TIME IT'S DIFFERENT

With the holds already chalked and visible, the friends prepositioned, and no extra weight on the harness, the climbing is very different. It’s exciting! Much less difficult than I remembered it. As always, the first ascent and the repeat of a route, even if just a single pitch, are two distinct worlds. Two radically different experiences. Elusive finger jams, full exposure. It almost feels like I’m on El Capitan in Yosemite. The rock is incredible. The first attempt fails, but on the second everything seems natural. One move after another, I climb with an unexpected lightness, and in a short time I’m at the end. What an incredible pitch! Now only one more remains. Silvan and Symon handle it. Instead of directly tackling the aid-climbed difficulties, they manage to find a way to get around them with a traverse to the right on the slab. They climb on millimeter holds, executing precarious moves. Now we can descend, with a long sequence of rappels to the base of the wall.

IN THE HEARTH OF THE GLACIER

After such an intense experience, the most natural thing would be to return home to our families. Yet we still don’t feel satisfied, so we decide to load up the kayaks and set out to explore a nearby fjord. Getting back in the kayaks is pleasant after the days spent on the vertical wall.

A kayak is truly an incredible means of transportation! It allows you to explore and reach even the most remote places on earth, environments that would not have been possible to observe on a sailboat. So we paddle into the fjord, following it to its uppermost reaches. We land at the highest point of the fjord and discover that, according to our maps, we should be in the heart of a large glacier. The fjord should have ended 5 kilometers earlier. We can’t believe what we’re seeing, and we’re even more impressed after checking the date on the map: only 20 years have passed!Where there should be a large glacier, today there’s nothing but the sea and a rocky wall above our heads. It’s not very high, but we still decide to climb it, following one of the many lines of perfect cracks that the rock offers us. A radically different experience than the first ascent of the route on the Siren Tower. Here the difficulty of the climb is well below our technical limit. We can place protection wherever we want and are caressed by the sun all day, providing us a pleasant experience in a spectacular setting. Given the conditions, we climb light and fast. We carry with us a couple of energy bars, a liter of water each, and the K-Performance Hybrid Jacket in case of a sudden change in weather. It weighs only 280 grams and is the perfect garment for climbers when the sun disappears and the wind rises.

Climbing on the wall feels almost like flying. A series of perfect lines that are relatively easy after our experience on the Siren Tower. This route is pure enjoyment; it’s the pleasure of climbing, of moving fast vertically following the weaknesses offered by the rock. One last moment of pleasure before we start to paddle toward Tasiilaq.

As soon as we leave the fjord, we’re immediately in difficulty. The sea is rough and the waves violently insistent along the stretch of coast that we need to navigate. We are lighter and more agile but also tired, and staying the course in these conditions is anything but easy. When we pull ourselves ashore at the end of each day, fatigue takes over, and just the thought of having to pitch the tent and prepare dinner creates additional stress. And as if that weren’t enough, in the last few days the fog also rolls in, making everything even more complicated. We’re often forced to stop and take breaks, both to recover our energy and to check the route and confirm that we’re on the right path. The air is so damp that it almost seems like we could cut it with a knife, which is why we wear the Sas Plat jacket, whose synthetic insulation means it stays warm even in these extremely damp conditions. Choosing the right gear is essential when tackling expeditions like this. The wrong down jacket would have left us wet and cold, putting at risk the last part of what, up to now, has been a fantastic experience. We often think about this as we speed along over the last few kilometers. The current quiets down as we come within sight of the port of Tasiilaq. The comforts of civilization await us, even if getting used to them again is hard. A distance of 170 kilometers was enough to deliver us to another world, a planet where nature wins — 170 kilometers that offered us a simple expedition for a perfect adventure.A journey along my personal road less traveled.