ODYSSEA BOREALIS

by Silvan Schupbach

In July 2024, the Swiss climber Silvan Schüpbach sets out to explore the east coast of Greenland with three other elite-level mountaineers. The goal? To open a new route on the virgin big wall of Droneren. Adverse weather and some close encounters with predators immediately push the adventure beyond the boundaries of a mountaineering expedition, creating a storyline worthy of the Homeric poems.

THE TEAM: NO “ODYSSEUS”

The point of an adventure into unknown territory lies in the how, not the what. Over the years, I’ve learned to live with the high risk of failure inherent in the pursuit of new challenges, feeding my ambitions with the seduction of the unknown. The expedition to the Mythics Cirque, which ended with the first ascent of “Forum” on the Siren Tower, had seared into my mind the conviction that “the value of the achieved goal lies in the journey undertaken to reach it,” to paraphrase Cavafy. This new journey reinforced my conviction, imparting a literal meaning to the passage in the poem “Ithaca.”

The final destination of this new journey is the unclimbed Droneren, an imposing rock tower nearly 2,000 meters high that juts out into the eastern fjords of the largest island in the world. It’s a hostile area in terms of the conditions and the approach; suffice it to say that the nearest village is a good 380 kilometers away. To reach the tower, we plan to paddle more than 300 kilometers by kayak, for a total of 600 kilometers round trip. The failure of the expedition undertaken by American explorer Mike Libecki in 2015 adds a further layer of challenge. Crossing the border of the known world, pushing into areas where others had failed — that was exactly what we were looking for!

Since 2019, I’d been planning an attempt with my partner Matteo della Bordella, but first the pandemic and later other vertical projects had shifted my attention from this dream.

Now that the necessary conditions are finally in place, Matteo and I decide to immediately bring in Symon Welfringer, with whom we had formed a very close group in opening the route on Siren. In addition, we also include in the team the guide and our great friend Alex Gammeter, whose experience will enable us to avoid dangerous situations. For more than a month, we’ll be able to rely only on the cohesiveness of the group. There’s no “Odysseus”; we’re all on the same level. We know that the lack of a leader could lengthen the process of making decisions (even minor ones, like those on where to stop to pee) and create some disagreement, but that’s the only way to be sure we’re making the best possible decision.

Beyond the “who,” climbing to the top of Droneren is mostly a matter of “how.” In addition to complete self-reliance, we all share the “by fair means” philosophy of exploration, a climbing style that’s clean from all points of view.

The large amount of ice that has accumulated in the Atlantic (experts say there hasn’t been an ice pack like this in at least 20 years) forces us to postpone our departure in the kayaks by a week. I have to smile now when I think back to when, comparing this new adventure to Himalayan expeditions, I told everyone that we wouldn’t have to wait long to get things moving. But despite this “false start,” we’re as giddy as children. The journey toward our entire mountaineering season’s goal has finally begun!

THE WRATH OF POSEIDON

The “Red House” in Tasiilaq is our base camp for the first few of the 35 total days of the expedition. Taking advantage (once again) of the hospitality of the manager, Robert Peroni, we pack food, clothing, and gear (a good 80 kilograms each) into the bins and warm up our forearms with the traditional evening card games. There’s always an air of magic inside that red building. We’re able to gather our thoughts, review the plan, and enjoy the feeling of natural warmth on our backs for one last time. The calm before the storm.

Meanwhile, the effect of the piteraq, the windstorm that had broken up the accumulations of ice and made the water navigable, has now finished. So we decide to rent a motorboat to reach Isortoq, our last contact with the known world. Beyond that population center, we’d have no internet connection for more than a month. Just us, the endless pyramids of ice, and satellite communication if needed.

Having left civilization behind us, it’s finally time to start paddling. On the first day, we pound out 45 kilometers, such is our desire to immerse ourselves in the chains of icebergs, which, placed sideways, form a central corridor that we slip into. In the first three days, we cover more than 100 kilometers, in an atmosphere of surreal silence interrupted only by the dipping and resurfacing of our paddles, the diving of a couple of massive killer whales, and the sudden breaking away of some masses of ice.

Over the next few days, navigation is complicated by the changing tide. Every morning is like a roll of the dice: we don’t know what unexpected event the day will hold. The first day, we get stuck in a frozen fjord after freeing ourselves from a maze of icebergs; the second, we’re almost trapped by an ice floe that forms suddenly. When the temperature rises and the surface ice melts, the waves build up to 3 meters, pushing us toward the high coastal fjords. At times like these, the idea of getting our hands on the rock doesn’t even cross our minds. It’s just the four of us humans, intent on understanding and adapting to the rules imposed by the immensity of the ocean.

On the seventh day of paddling, when we’ve already covered more than 200 of the 300 planned kilometers, a fierce storm strikes, forcing us aground near an old Viking settlement. I’d seen something like this only in Patagonia: winds of more than 100 kilometers per hour, fragmented rocks flying over our heads. In total, the storm continues for more than 60 hours, ripping our tents and causing us to wonder whether we’d even survive! Just as Odysseus fell victim to a terrible storm unleashed by Poseidon, we too have been struck by the wrath of the god of the seas. We’re experiencing a real Odyssey!

On the third day, the waters become calmer, so we decide to start paddling again — nonstop to make up for lost time. When everything seems to be going smoothly at last, we’re caught in a second storm. This time it’s shorter, but I also remember it as more severe. Emotionally, it’s a difficult time. Waiting too long means taking away precious days from our attempts on the new climbing route, and thus returning home empty-handed. The meteorologists we consulted with before our departure spoke of low rainfall and rising temperatures in August in the subarctic area, so this is not exactly what we expected. After carefully assessing the risks, we decide to go ahead. Finally, luck and the weather really seem to be on our side. On the tenth day of paddling, we reach our goal, our Ithaca: Skjoldungen Fjord.

THE STORM OF ZEUS, THE WINDS OF AEOLUS

Skjoldungen Fjord is an Arctic oasis. The mild climate in this area allows for lush vegetation, enhanced by clear streams and rivers. All around are gorgeous open valleys and mountains that rise above 2,000 meters: a picture-postcard idyll. But this breathtaking landscape serves as a backdrop to hostile terrain. In the 1970s, the only Inuit settlement in the area was dismantled by a government order. Prohibitive conditions made procurement of supplies and subsistence impossible for the inhabitants. In 2015, the adventurer Mike Libecki completed the first ascent of several routes that stand out in the area, but he was obstructed by the ice pack and didn’t have time to make any attempts on Droneren.

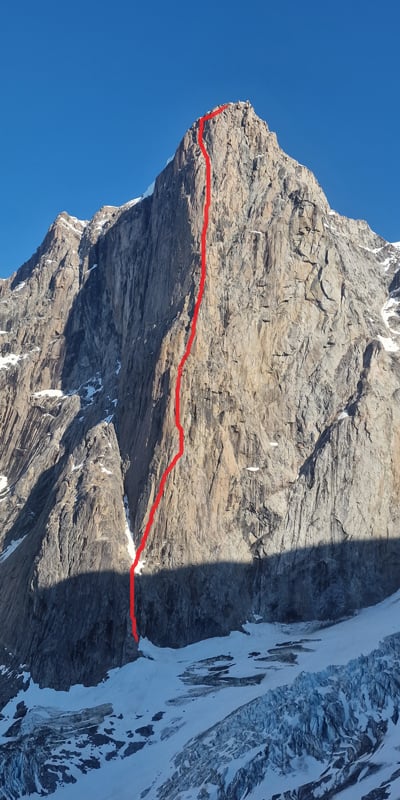

There it is at last, right in front of us, 10 years since it was last visited. Droneren’s northwest face soars up to 1,980 meters, untouched and dazzling in the warm sun, further feeding our ambitions. At the sight of the wall, the rationality we’ve imposed on ourselves is briefly overcome by exhilaration. The approach is not the easiest, and besides, we need to consider our available resources: the storm has depleted them more than it should have. After a few hours of rest, we toss our gear over our shoulders and set off.

We go up the valley floor and then climb over moraines and firn fields until we’ve passed the glacier that lies immediately below the wall. Shortly after we get ourselves organized, a huge boulder breaks away from the western area and crashes spectacularly at the foot of the wall. We respond to this welcome by deciding to stay on the central pillar, the most exposed part. The next morning, I identify a line that cuts right up that pillar. The starting point has been established; all we can do now is cross our fingers and hope for a window of good weather. In reality, we know we don’t have much chance of climbing in the next few days. Taking advantage of the last day of good weather, Matteo and Symon are able to put up some fixed ropes on the first part of the wall. After two days of bad weather, Alex and I have the honor of continuing. We insert four shallow peckers in the most complicated sequence of the route (7b), where the cracks had disappeared. It’s not the hardest, but it is one of the most aesthetic pitches I’ve ever equipped in my life.

The second stretch of bad weather allows us to process what we’ve completed so far. While we wait for the sky to clear, we meet a group of curious visitors from a cruise who’ve come to see us at base camp, offering us a case of beer. But our time is running out: there are just five days left to finish the project. We don’t even start the third attempt. During the night, a significant amount of snow falls on the summit, and sheets of ice form on the wall as well. During the fourth attempt, a piteraq suddenly rages, causing dozens of rocks to roll toward us. One of them cuts the rope that Symon is climbing on. Fortunately, he’s fine; he’s still clipped in. The storms that have struck throughout the expedition, and the destructive effects of the wind, remind me of the passage in The Odyssey in which the Greek hero’s companions open the wineskin in which Aeolus had enclosed the winds, unleashing the wrath of the elements. We have the feeling that the gods of the sky don’t want to let us achieve our mountaineering season’s goal.

For the umpteenth time, we beat a retreat back to base camp. In a few hours, our mood has plummeted, as have our chances of success. We’re now faced with a decision that we’d considered before we left but that would inevitably ruin the expedition to some extent. Should we return to Tasiilaq immediately, or allow ourselves one last climb and then recover in the middle of the ocean, given the limited time available to return to Tasiilaq? We choose the second option, ready to gamble everything on a final attempt.

RETURNING TO ITHACA

1Odyssea Borealis |

With the fifth attempt, we go all in. We have only three days left to climb to the top of Droneren. To be precise, two days to free the new pitches (nearly 500 of the 1,200 total meters of the route’s length) and a full day to finish the route, rappelling down safely. Now the sky seems to have finally calmed down. Symon and Matteo advance quickly on the virgin surface, while Alex and I carry the two inflatable portaledges and the rest of the ropes. On the wall we move as a real team, energizing each other. That day, we put our hands on the rock and realize our dreams. We’d never pushed ourselves so far before. Falling asleep under the stars, which finally seem to align, is an indescribable thrill, accompanied by that feeling of excitement that precedes something big.

The following day, it’s Alex’s and my turn to lead operations. On the last part, the snow from the previous days has settled in, creating a section of mixed climbing that is treacherous, to say the least. Thanks to Alex’s endurance, we make it through the last few pitches as well (35 in total), leaving the rocks below us. We pass the large ice cap almost without realizing it — so great is our eagerness to reach the highest point — and, with a cry of relief that takes our voices away, we shout our joy. The summit of Droneren! Needless to say, the view from up there will stay with us forever. From the Greenland ice cap to the towering mountains and, beyond, the Arctic Ocean. Our gaze keeps wandering, lost, unable to stay still. According to Matteo, it’s a picture worthy of the horizons that only Cerro Torre can provide. We begin to descend under the last light of the day, returning to the bivouac. Our bodies don’t want to think about resting; the adrenaline rush continues for several more hours. As the day comes to a close, the distinctive green wave of the northern lights paints the sky above us. In a few hours, failure has been transformed into a resounding success, one that nature is also contributing to — an unforgettable life experience. Our route is quickly christened: “Odyssea Borealis”!

But the expedition can’t be considered finished until we get back to Ithaca. After our triumphant return to base camp, we learn that it’s not possible to go back directly from Skjoldungen. We must paddle for another three or four days, covering at least half the distance to Tasiilaq. While we’re preparing our kayaks, a polar bear approaches, coming within a few dozen meters of us. He is powerful and intent on making our acquaintance, but we have other ideas. I fire a couple of shots into the air to drive him away. The third one has the desired effect.

The last few days of navigation proceed smoothly. The undulating motion of the waters gently accompanies our fleet of kayaks. As we proceed northward, the intensity of the wind diminishes and we begin to glimpse the fjords of the Irminger Sea. Our “Pillars of Hercules,” marking the limits of the known world. During the night we take turns on guard duty, worried that we might run into one of the polar bears we’d encountered (the one we saw near base camp at the wall was not the only one). After several attempts, on the 32nd day of the expedition, someone comes to pick us up. Our odyssey to the far north ends here, but it lives on in this story and in our memories!